- No products in the cart.

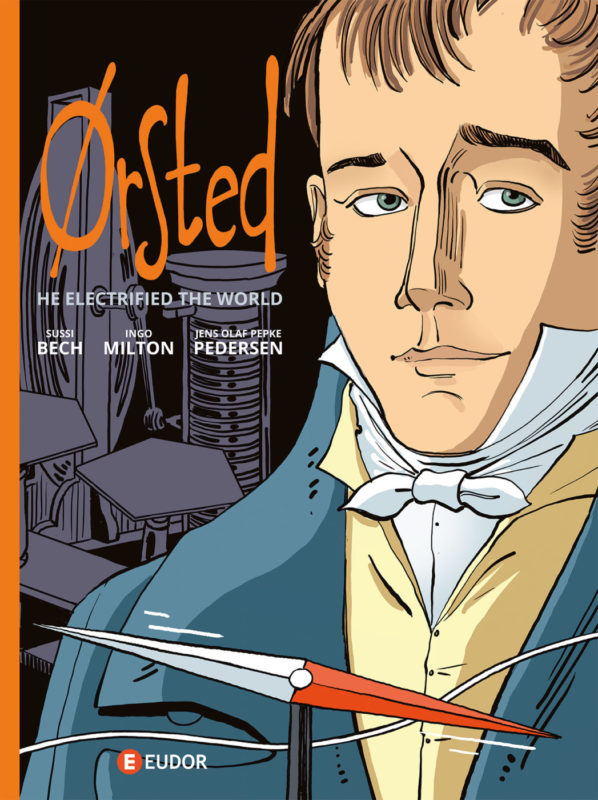

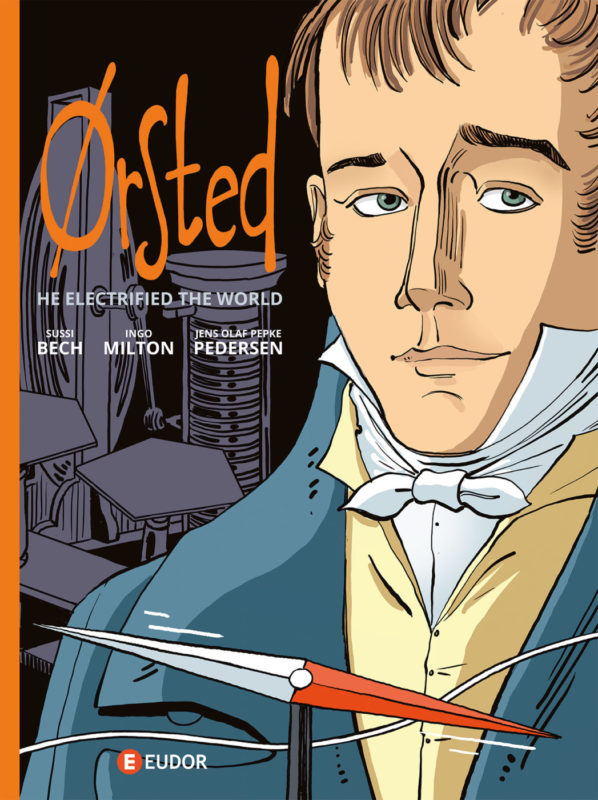

The 80-page comics biography Ørsted. He electrified the world by Sussi Bech, Ingo Milton and Jens Olaf Pepke Pedersen, which came out in June 2020, has turned out to be that year’s best selling comic produced by Danish authors.

The 80-page comics biography Ørsted. He electrified the world by Sussi Bech, Ingo Milton and Jens Olaf Pepke Pedersen, which came out in June 2020, has turned out to be that year’s best selling comic produced by Danish authors.

A 6th printing has just been ordered with more than 5,000 copies sold so far.

So who was this man? We asked Ingo Milton to tell us why Ørsted’s life story still fascinates us today.

Hans Christian Ørsted — the discoverer of electromagnetism

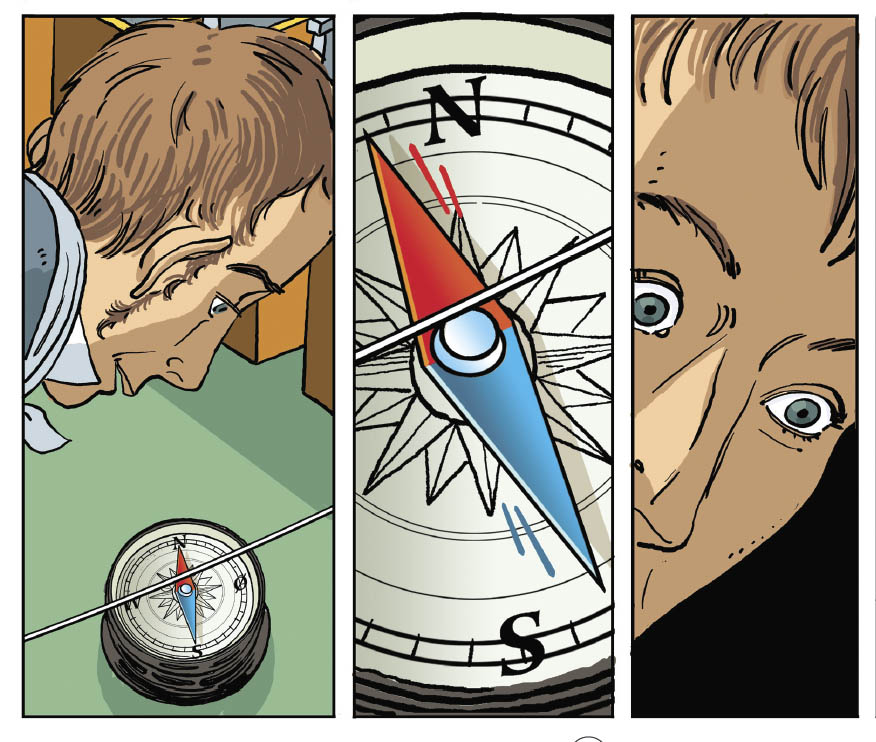

Hans Christian Ørsted is a Danish physicist known for being the first to describe the effect of an electric current on a compass needle. He did that in 1820 and called his discovery ‘electro magnetism’.

This was the start of intense studies by other scientists which eventually led to the harnessing of electricity as a power source and the total electrification of modern-day society.

Ørsted is also a great eye-witness guide, to a time when scientists discovered laws of nature and saw them as proof of a greater purpose behind creation.

Ørsted was Danish, so of course, his achievement is best remembered in Denmark, where every schoolchild is presented with his simple experiment at least once in their curriculum. That was also the extent of my knowledge of Ørsted, when our co-author, Jens Olaf Pepke Pedersen, suggested that it was time Ørsted’s life was told in the form of a graphic novel.

His letters won me over

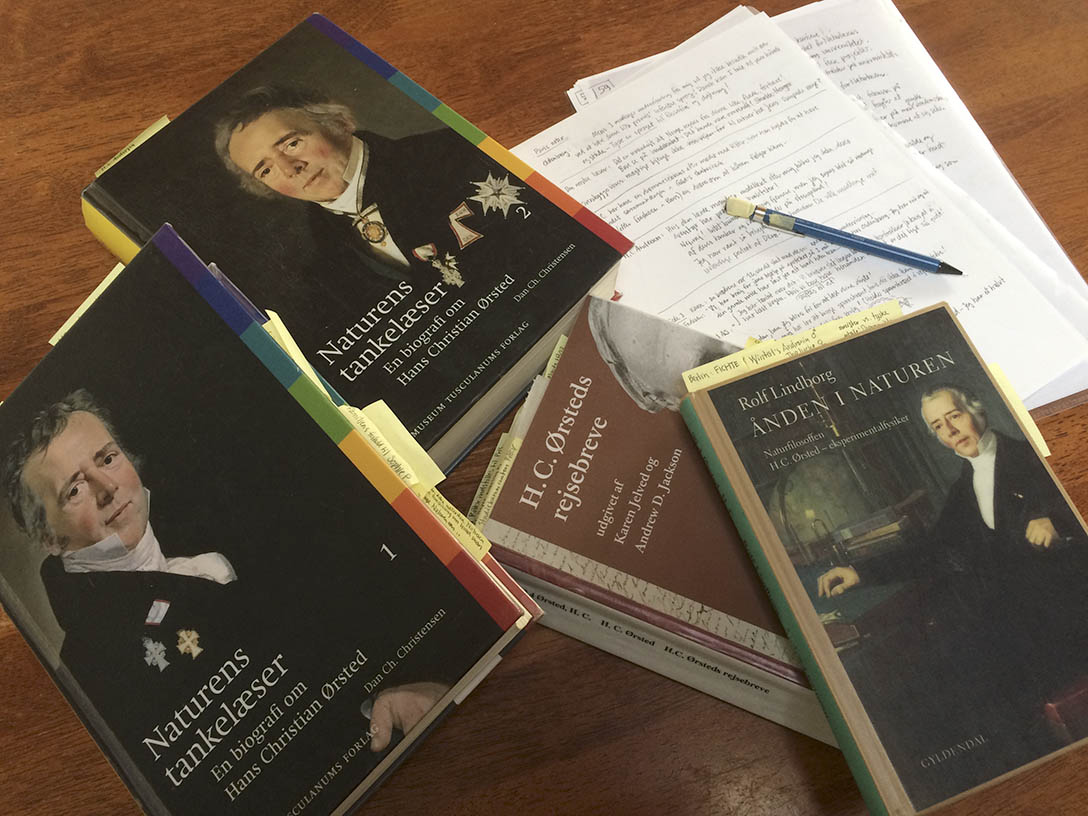

So I sat down to learn more about this scientist from over 200 years ago. Fortunately, he wrote a lot of letters, and it was the letters from his first, three-year European trip 1801-1804, that struck me as remarkably alive and vibrant.

Ørsted was commissioned to explore and bring home knowledge of chemistry (ceramic glazes and beer-brewing techniques), but that didn’t prevent him from looking up the biologists, physicists, historians and writers he had read about at home. He went to concerts, theatres, lectures … any cultural event that came into sight. He took it all in and wrote home about it with enthusiasm and cunning observations.

- Page from “Ørsted”: Carnival in Paris. Click to enlarge.

- Paris around 1800 AD.

- Paris around 1800 AD.

He arrived in Paris in December 1802 not speaking any French, but by spring 1803 he had learnt the language well enough to participate in the city’s bustling life. On Shrove Sunday he threw himself into Paris’ famous carnival.

He wrote home: “The busy boulevards are dominated by coaches filled with all kinds of masked people: Ladies as men, men as ladies, as monks, as Chinese, as orientals, but most as harlequins. In the evenings, public houses are overcrowded with masked dancers. Many of the ladies here are as public as the events, but they are all dressed as well as the finest ladies at our balls at home!

Rumour has it, that Bonaparte has donated a large number of masks to the police, so they can observe while participating …”

The visual reference to the Parisian carnival can be found in newspapers from the period, and of course, it is recreated in Marcel Carné’s movie “Les Enfants du Paradis”, so it was easy to put our protagonist at the scene, thinking he recognises his fiancé from back home …

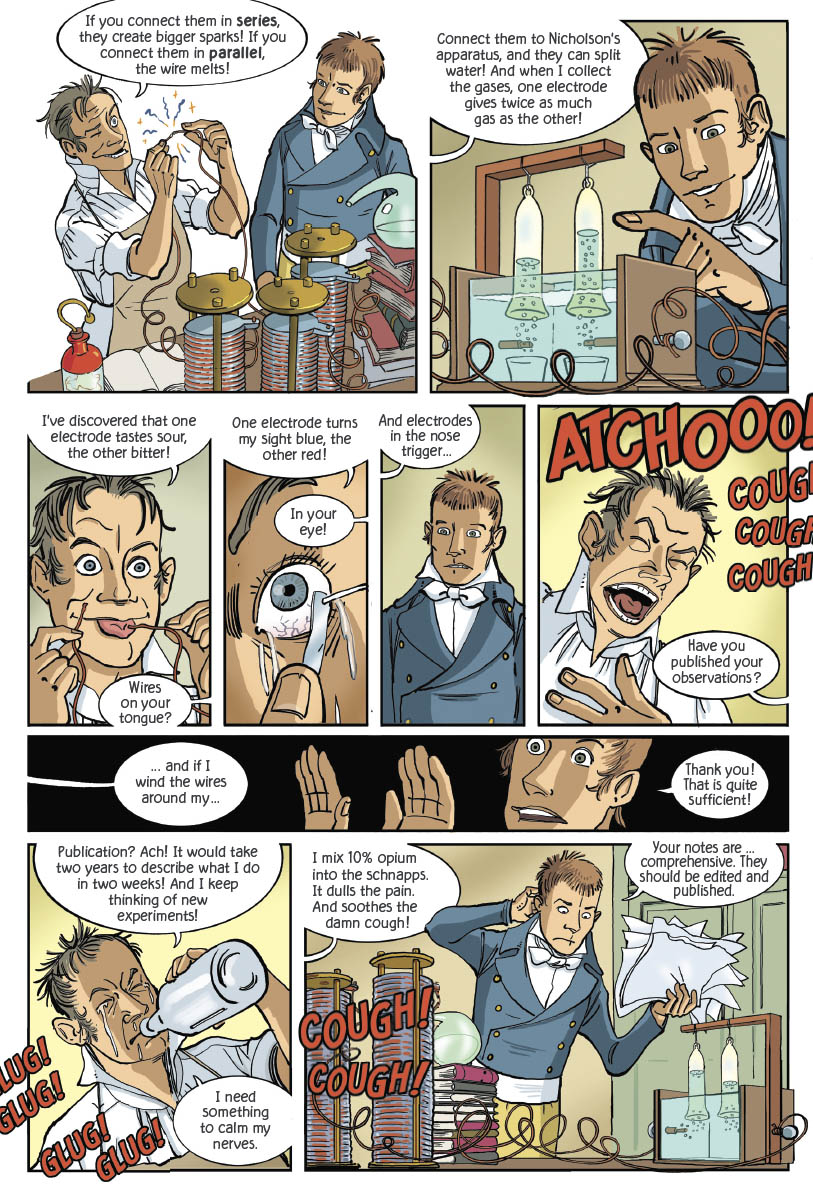

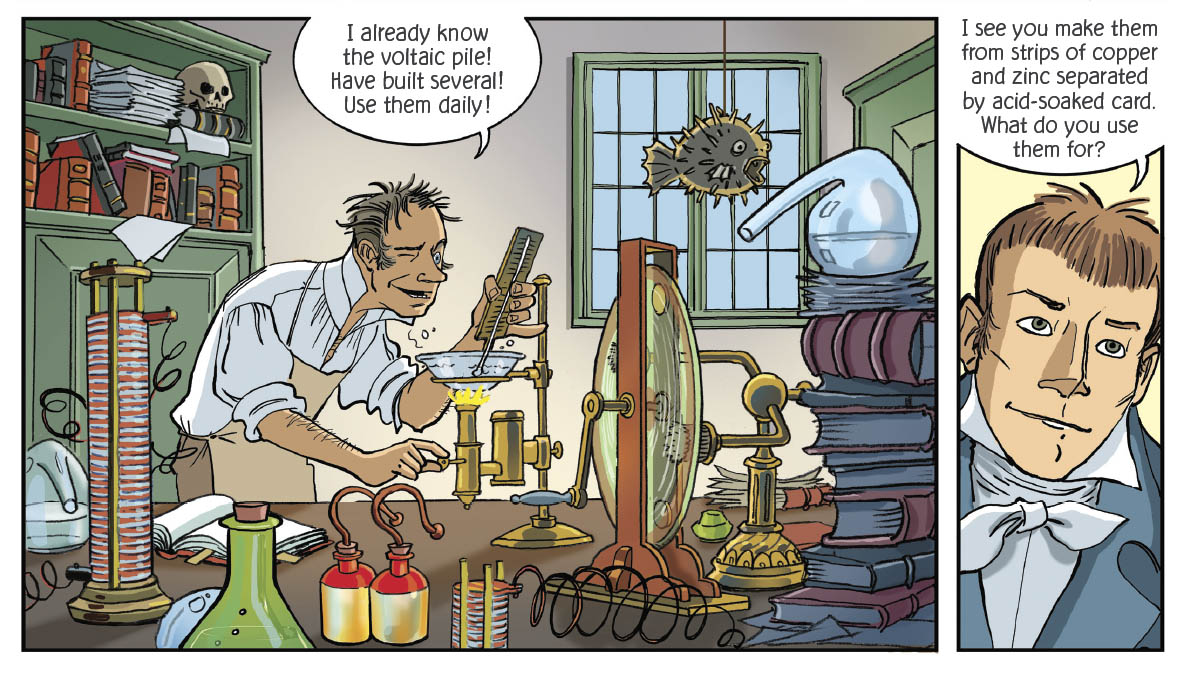

H.C. Ørsted visiting his German colleague Johan Wilhelm Ritter.

The mad German scientist

On his way to Paris, Ørsted befriended the German scientist Johan Wilhelm Ritter, who from a scriptwriter’s point-of-view was a gift to the story.

Ritter fits the cliché of a genius scientist who is so uncompromising that it borders on madness. Ritter and Ørsted were both curious about the applications of an invention that had been published only a couple of years before by an Italian, Alessandro Volta: The world’s first battery – the Voltaic pile.

Ritter and Ørsted had already, on their own, built versions of the battery and explored some basic effects of the pile’s current: heat, light, splitting of water into gasses … But Ritter felt he needed more sensitive instruments, so he started to use himself and his own body as a guinea pig. Eyes, nose, mouth and skin were tested against the new electric current.

Ørsted didn’t share Ritter’s enthusiasm for this approach, and we had fun showing this disagreement in a subtle way. But Ørsted does see the genius behind the obsession and offers to present some of Ritter’s other experiments to fellow scientists in France. More importantly, Ørsted and Ritter both felt their discoveries were proof of a divine, unifying force behind the dynamic mechanisms of nature, and they spent days discussing these ideas.

Defeat in Paris?

When researching Ørsted’s life we came across a narrative claiming that Ørsted was ridiculed by the scientific establishment in Paris because, in 1803, he conducted a failed experiment to demonstrate a new theory of Ritter’s: that Earth had two electric poles beside the well-known magnetic poles.

Reading Ørsted’s letters you get a feel for his personality, and this narrative just seemed out-of-character, because Ørsted, who grew up working in his father’s laboratory, was a skilful demonstrator, and he would never conduct an untested experiment before a larger audience.

Rather, this storyline of a devastating defeat in his youth seemed contrived in order to lend more drama to Ørsted’s life, ending with his big, successful discovery later in life.

- Ørsted at Société Philomathique. Page from “Ørsted”. Click to enlarge.

- Ørsted was welcomed in Paris by his colleagues at Société Philomathique. Page from “Ørsted”. Click to enlarge.

- Société Philomathique’s report from it’s sessions with Ørsted. Click to enlarge.

Fortunately, the Société Philomathique in Paris published first-hand records of their demonstrations and they have been scanned and put on the internet, so finally, we found the report from the session of ’24 Vendémiaire year 12′ (dated after the French Republican calendar (1793-1805)) which translates to ’17th of October 1803′. This proves that no ridicule took place. The Galvanic Commission even gave Ørsted 10 days to present Ritter’s other successful findings, and after that the young Ørsted spent 9 days with the most prominent French physicists, Jean-Baptiste Biot and Charles Coulomb, to test for Ritter’s electric poles.

The verdict was not negative, just inconclusive. Ørsted left Paris on the best of terms with his colleagues, and this served him well 17 years later when he published his discovery of electromagnetism.

Fire from the sky

Ørsted lived through a period of international strife in Europe. A great contention played out between France and England and though Denmark tried to keep out of the conflict, it was attacked by the British navy in 1801 and 1807.

- Hans Christian Ørsted during England’s bombardment of Copenhagen in 1807. Page from “Ørsted”. Click to enlarge.

- Hans Christian Ørsted during England’s bombardment of Copenhagen in 1807. Page from “Ørsted”. Click to enlarge.

- The Congrave Rockets of the British Navy.

The English wanted control of the Danish merchant fleet, and when that was refused, they attacked Copenhagen in history’s first terror bombardment of a civilian city. Ørsted and his brother stayed in the city during the attack, where the English used a totally new weapon: incendiary rockets. The fires were so extensive that the Danes surrendered their fleet after three nights of bombings.

Ørsted and his family survived, but the defeat started a national economic crisis that brought Denmark to bankruptcy seven years later.

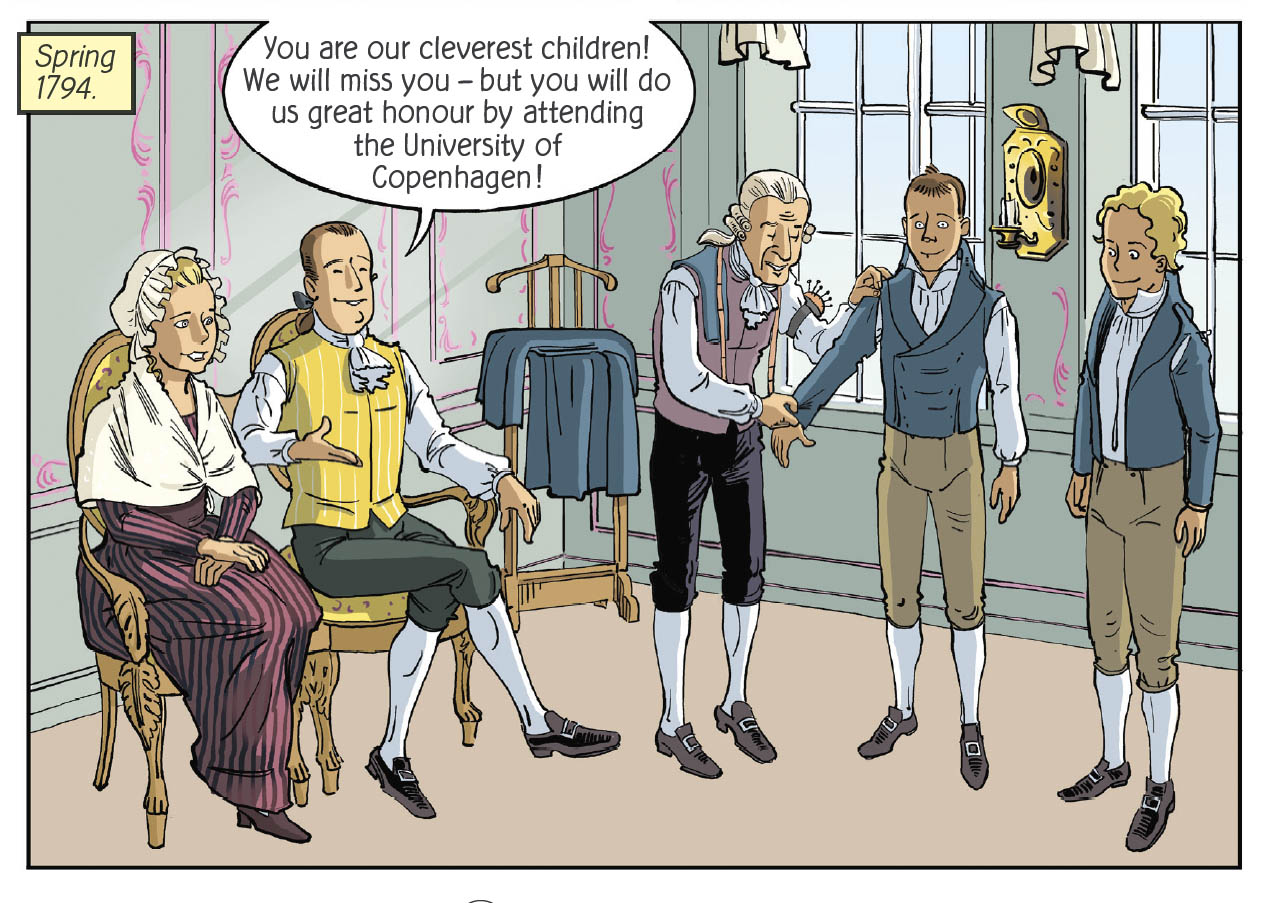

A young Hans Christian Ørsted and his brother Anders (later to become Danish Prime Minister) dressed up before going to Copenhagen to study at the university in 1794.

The right fashion

Part of getting the right ‘feel’ for a historic period is the right clothing. Even men’s fashion changed greatly during Ørsted’s life. He was born at the time of powdered wigs and knee-breeches, but by the time he became a professor the fashion had changed to natural hair and long, straight trousers.

Hans Christian Ørsted and his family in 1820.

Homemade batteries

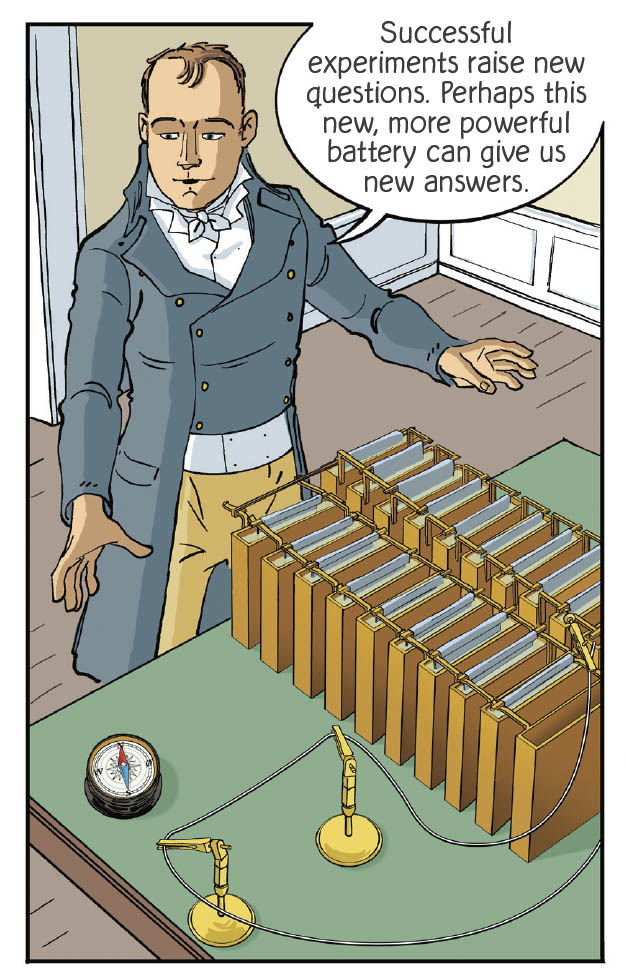

Since Alessandro Volta’s invention, in 1800, of the electric battery in the form of a stack of copper and zinc disks, Ørsted had built his own batteries and gradually improved the design to increase its power.

Ingo Milton.

H.C. Ørsted.

Batteries are such a common commodity in our day that it can be hard to grasp the concept of having to build your own. To address this, we made a video for the complimentary educational material to our comic, where we show how you can build your own battery out of lemons.

But for Ørsted, lemons were not powerful enough. By 1820, his battery consisted of copper tanks filled with acid in which zinc plates were suspended. This was what he used at a lecture in April 1820, when he decided to test the possible effect of an electrical current on a compass.

At first, the movements of the needle seemed confusing, but three months later he found a rule that could predict the movements.

Once Ørsted realised the scope of his discovery, he hurried to write a description in Latin and sent it to 40 colleagues all over Europe, many of whom he knew from his earlier travels. Within six months his achievement was generally acknowledged.

The crucial moment in 1820 when Ørsted discovers the connection between Electricity and Magnetism.

Ørsted and Hans Christian Andersen

In the following years, Ørsted left it to others to explore electromagnetism further. Especially Michael Faraday, André Ampère, and James Maxwell are rightfully remembered today for their groundbreaking work.

- Hans Christian Andersen. Click to enlarge.

- The first meeting between H.C. Ørsted and H.C. Andersen. Page from “Ørsted”. Click to enlarge.

- The first meeting between H.C. Ørsted and H.C. Andersen. Page from “Ørsted”. Click to enlarge.

At this time Ørsted had engaged himself in many other fields. He was a professor at the university, gave public lectures, founded a scientific society and took part in the literary scene in Copenhagen. As such, he was paid a visit in 1821 by a very young Hans Christian Andersen.

Though the young Andersen was lacking in social skills, Ørsted took a liking to him, and eventually, he became a weekly dinner guest in Ørsted’s home. It turned into a lifelong friendship, and Ørsted was among the first to see the qualities in Andersens’s stories for children. Once, when the young poet was devastated by a negative review, he consoled him: “Your novels may yet make you famous, but your fairy tales will make you immortal.”

Ørsted believed that as we come to understand the laws that define the natural world, these laws will also pertain to defining true beauty in the arts. For this reason, he advocated that the natural sciences ought to play a greater role in fiction and poetry.

Hans Christian Andersen came to share Ørsted’s fascination with technical progress and his view on the connection between arts and science. He even let Ørsted appear as an allegorical character in some of his fairy tales, so maybe Ørsted did achieve some sort of immortality in the end.

Danish radio host Peter Lund Madsen (left) interviewing the Ørsted team, Jens Olaf Pepke Pedersen, Ingo Milton and Sussi Bech.

Breaking the barrier

When our book was first published we were still wondering, if a Danish audience would care about the life of a scholar two centuries ago? The book took off with good reviews all over.

Even the ‘Engineering Weekly’ newspaper was very positive and the first print run of 2,100 copies was sold out in ten days. We gave an hour-long interview on Danish national public radio about Ørsted and his discovery. After that, demand for the book rose to new levels. We seemed to have broken the barrier between graphic novels and the general public. Grandparents bought it for their grandchildren, all the graduating pupils on the birth-island of Ørsted received it as a farewell gift. Even people without any interest in physics bought it for its portrayal of the period that is now known as the Golden Age of Danish culture.

The book is now in its sixth printing and the sparks are still flying.

Data

Data

1 book

80 pages (63 comics pages + 12 page illustrated appendix)

23.0 x 31.5, hardcover

Published in Danish and English

Ages 13 and up

- Contact for Foreign Rights: Ingo Milton

- Reading sample: PDF in English

New book in preparation for 2022

The team behind »Ørsted« is now working on a new book related to the history of Physics. The comic book will see publication in Autumn 2022.

Sussi Bech

Sussi Bech

A 1983 graduate from the School of Applied Arts in Copenhagen, Sussi Bech is an award-winning cartoonist living in Denmark. Her most popular graphic novel is Nofret – 13 volumes so far – which stars a young Egyptian girl in the land of the pharaohs and combines her adventures with historically accurate depictions of ancient Egypt. Sussi Bech has won several awards for her work.

Ingo Milton

Ingo Milton

Graduate from Design School Kolding.

Founding member of Gimle Studio in Copenhagen 1980.

Since 2006 he has collaborated with national museums using comics to visualise the lives of people who went before us: Iron age tribes in East Jutland, Saints from Jacques de Compostella to Santa Claus, Seamen in the Caribbean, crusaders, carpenters and scientists alike.

This work earned him the Hanne Hansen award in 2014.

Jens Olaf Pepke Pedersen

Jens Olaf Pepke Pedersen

Born in 1958. He holds a PhD in physics and is a senior researcher at the Danish National Space Institute, where he conducts research into climate change. He has previously worked at the universities of Aarhus and Copenhagen, the CERN research centre in Geneva and several US universities.